|

Looks Like it

Sounds--

or, those bizarre squiggles we call music.

(part one)

Why do we

write music the way we do and is it actually the

best method? Dare we ask?

part two

part three

|

When the ancients

wanted to refer to the sun, they simply drew a

picture of it.

|

|

This is a far cry from writing a

combination of squiggles and lines, as we do today. The

word SUN doesn't actually look like the sun; we wouldn't

know that it had anything to do with the sun at all

unless we were told. Each of the letters represents a

specific sound, but that still doesn't mean when you add

them up they are going to automatically suggest

anything.

|

SUN

|

These two very

different approaches to language have their

obvious strengths and inevitable weaknesses.

There is something lost in not being able to

graphically represent what you are talking

about. Clearly a language like that is much

harder to learn, endless combinations of

arbitrary lines and curves with their numerous

rules for organization, chances for

misspellings, bad grammar, and the like make for

some of that celebrated "modern anxiety." And

you don't get to admire the pictures.

|

| I'd like to

see you try, however, to represent something

like "inevitability" with a picture.

Wait, I just thought of one. How about a guy who

has just stepped off a cliff? The only problem

there is that pretty soon they'll also be using

that one for the word "gravity", maybe the word

"panic" and eventually, "lawsuit", given the

various needs of our contemporary society. So

the simple one-to-one relationship between a

thought and its picture will get spoiled anyway.

Leave it to us "moderns" to ruin that fun.

|

"Inevitability"

|

The charm of a

pictorial language like hieroglyphics is that

everything that needs to be communicated can be

represented graphically, and means exactly what

it looks like. None of this "except after g" or

"sometimes y" stuff we have to remember today.

The sun means only one thing, not something else

if you draw a picture of a polar bear after it.

Once complexity (or abstraction) rears its (for

some) ugly head, you have to start looking for

context and overall meaning and you still might

not get it right away.

|

The word

"phonetically" means "how it sounds" or, to

spell a word using letters that obviously make

the sounds of the word. But, as is often

pointed out, the word "phonetically" itself,

isn't. If it was, it would be spelled

"fonetikalee".

In a

pictorial language, putting a polar bear next

to the sun could mean the bear was sunning

himself, or trying to eat the sun, or running

after the sun, but it would not mean, say,

swimming pool. Each character, both the sun

and the bear, are still suns and bears,

regardless of their relationship to each

other. You don't add two characters together

and they become something totally different.

But, for some reason, in modern English, you

put an H next to a P and they cancel each

other and become an F! How does that make any

sense?

|

Not that modern language has completely

lost its pictorial element. We still use metaphors and

figures of speech that present a strong mental image

that creatively crystallizes abstract meaning. If we

say, for instance, that somebody is "out in left field"

we have caused the mind of the listener to glow with an

image that seems to fill in the need for a sense of

being able to 'see' what we are talking about. When we

refer to somebody whose views or behavior is a long way

from normal or from what we agree with, if we mentally

paint that picture, it gives our meaning additional

life, punch, or clarity.

Written music began life as a kind of

pictorial language--then things started to get rather

complicated.

| When, in the

ninth century, a fellow named Guido managed to

devise a system for actually writing music

down--you can read about that interesting story

elsewhere

on this website--the

method he came up with was pretty simple. Put a

line on a page. Now put a blob on the page

representing a note. If the note is above the

line it is higher than if it is on the line,

still higher than if the pitch is below the

line. High notes mean higher on the page.

Actually, what we really mean by high notes is

that they are vibrating more times per

second--sound is vibrating air, after all--but

people have always referred to high notes and

low notes as a matter of course (it takes more

effort to pop off a 'high' note because your

voice box has to flutter faster), and when you

go for a high note, people are much more likely

to gaze up at the ceiling than they are to look

at the floor. Besides, they didn't have

scientists to tell them all this when Guido was

around. |

the Guidonian hand

(a method for learning the

notes)

|

Imagine. It took nine centuries into

the "modern era" to come up with something that simple.

And there were untold centuries before that too, of

course. Several millennia for humans (Western Europeans,

anyway) to figure out how to write down something they

could already do aurally, even while they could

write--only a few of them, of course--in their own

native languages.

I remember being taught in school that

the origin of writing things down probably began as a

result of the need to keep written records of things

like taxes and what not. The real important stuff like

how much the king had in his royal treasury. Music

didn't turn a profit then anymore than it does now (ok,

I'm splitting hairs; I'm leaving aside the bulk of our

commercially successful but artistically thin

recordings) and it does not seem to have been of much

concern to anyone that it be preserved for posterity or

even so it could be shared with anybody who wasn't the

king of that immediate area.

Well, I'm oversimplifying. A lot. But

the fact remains that music was not written down for a

while in western cultures--at least that we are aware

of. There are some fragments of ancient Greek music--one

famed specimen is chiseled into a rock and is called the

"Hymn to Apollo." I've seen it. There do seem to be some

musical instructions, but these are mostly circles and

triangles and other shapes above the words which give us

no idea of what the music was supposed to sound like.

But the beauty of Guido's system is

that once a one-note to one

position-on-the-system-of-lines can be established, you

can sing anything, whether you've heard it before or

not. C is C. Or, as Guido would have thought of it, Ut

is Ut. Good thing somebody came up with a replacement

name for Ut.

Systems do have a way of becoming

unpleasantly obsolete, however. As always, some things

happened to music that Guido would never have thought

of, and in some ways his system proved to be

surprisingly adaptive and to hold up well even after so

many later changes, and in others, the system was

strained almost to the breaking point.

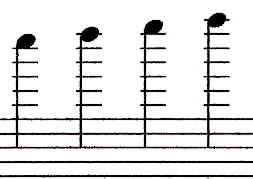

When Guido came up with his system, it

was the human voice, that oldest of musical instruments,

that was being taken into account. He didn't have a

piano with a range of eighty-eight notes to worry about.

Most people can't sing more than an octave or so, maybe

two, unless they are trained singers. The church music

of the time did not jump around very much, and mainly

confined itself to an octave. Eight notes. So having

four lines, and three spaces in between the lines seemed

like plenty (the space above the top line being

available for emergencies!).

______________

______________

______________

______________

It later turned out not to be. No

problem. A fifth line was added to the staff (which is

what we call that flock of lines) and now there is room

for nine notes, which is a little bit short of 88 if you

are scoring at home.

______________

______________

______________

______________

______________

There are ways to get around this

difficulty. One of which is to simply add staffs

together. Once you yoke two of your systems together,

you suddenly have space for around 19 notes. Now we are

getting somewhere.

______________

______________

______________

______________

______________

______________

______________

______________

______________

______________

Of course, in order to avoid eye-strain

from having to determine exactly which line that a note

is on--of the ten that seem to be run together-- we're

going to actually create a little break right in the

middle. Space is a nice way to clarify things. Besides,

I dare you to decide, at a moment's notice, whether a

note is on line 6 from the bottom or 7 from the bottom.

So let's split things up for clarity's sake.

______________

______________

______________

______________

______________

______________

______________

______________

______________

______________

Technically, the two staves are one

continuous system, and there is room for one

invisible line between them. This, added to the

spaces immediately above that line and below it, give us

room for three notes that are actually between the two

staves. We don't use this line unless we need it to put

a note on, and that means that unlike the others, which

run continuously whether we need them for reference or

not, this one only pops up when needed, lasts a little

over the length of the note itself, and disappears. It

is like the volunteer firefighter of notes.

|

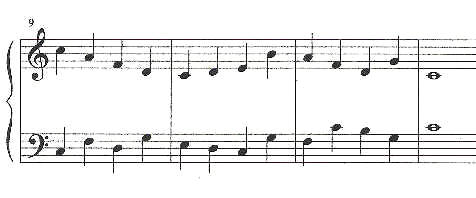

In

actual practice, the two staves are separated

by additional space for ease of reading, and

so that we can jam several other kinds of

musical instructions in there! (or lyrics) The

two notes at the end are actually the same

note--both the additional line extending above

the bottom staff and the additional line

extending below the top staff are known as

"middle c" and the next note above or below

them falls on the space adjacent to the first

line of the other staff. So I suppose all that

space you think you see between the staves

doesn't really exist! I mean, if you're into

quantum physics and whatnot.

|

This little line of ours in turn

creates a new kind of being which we call a ledger line.

If we can extend the staff toward the middle, why not

above and below? And why stop at one? Ledger, or

additional, lines can be added to the bottom of the

lower staff, and the top of the upper staff to extend

the number of notes we can call into being. They behave

exactly like the one in the middle, and only show

themselves when necessary. However, a good many

composers have determined to abuse a good thing when

they have it, and frequently use four, five, or six

ledger lines with impunity. You are now perceiving that

this may make things a bit hard to read. Trained

musicians, having long become accustomed to the system

of five lines and four spaces, can instantly read a note

based on its location, just like you know what four plus

four is without having to stop and consider the issue

(let us hope)--but extending too many lines in one

direction or another makes things too confusing, and

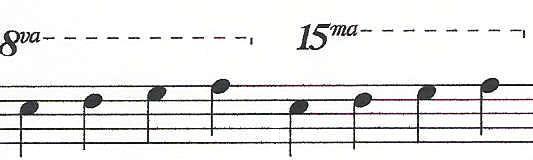

besides, there is a better method. It is called 8va, or

octave in altissimo--that is, an instruction to the

performer to play what he sees on the page eight notes

higher than it is actually written. Since musical

pitches have only seven names -- A through G

(again, what simplicity!) the eighth will again bear the

same name as the first, when the series starts over. It

will also, due to its association with a particular

group of raised black keys, "look" the same as all of

the other pitches on the piano with the same name. Young

pianists often spend their first lesson trying to find

all of the "Cs" and "Es" on the piano.

Thus it is a relatively simple thing

for a pianist to see an 'A' in one part of the

piano, and to substitute for it the next 'A' above that.

If this is still not high enough, the composer can write

15ma, indicating the note two octaves higher. Not

sixteen, mind you. If you want to add an octave to the

one you've already prescribed you have to remember that

the bottom note of the succeeding octave is actually the

same one as at the top of the first (abcdefgAbcdefgA)

and not count it twice. If it is too late at night and

you would rather not do the math, just trust me. It is

15 notes.

Now with that kind of flexibility we

can put all kinds of high and low notes onto just two

staves joined together. Often ledger lines are used for

notes hovering just above the staff--two or three lines

is quite common, but six is just plain ridiculous. So if

you have a composer cousin, or dog, or neighbor's dog,

or aunt's sister's neighbor's dog's flea's half-uncle,

please tell them not to use too many ledger lines. I've

premiered several new works in my time, and having to

pick my way through all of those ledger lines when there

is a perfectly good alternative just frustrates the snot

out of me.

Our glorious system of random

lines can tell us which notes are higher than which

others, but technically, they don't point to a

specific pitch; merely the relationship between the

various pitches. Sure, the note above the line

is higher than the one on the line, but which note is it

really? Which piano key should I play, in other words.

Would you want to forever be known, not by a

particular name, but only as the person who lives next

to Fred? Your whole existence determined by your

relation to somebody else? No individual definition,

no fixedness. That fixedness is what clef signs give

us; we'll take these up in part two. They may be silly

looking, but they are very important. There are

several of them, and they each change the meaning of

the lines that follow them in their own way. Thus a

note on the bottom line may be an 'E' in one clef, but

if you throw another one at it, it becomes a 'G'. And

just like that we have crossed the divide from that

happy and innocent time when a thing was a thing no

matter what, and when it changed its meaning according

to the context. Just like the primary difference

between hieroglyphics and English (as we superficially

understand them, anyway). But we will cover this in

the next article, so if you want to imagine that the

sun revolves around the earth, musically speaking,

that the center is the center and that's that, until I

get around to the next installment, why, go right

ahead. I'll understand.

on to part two: clef signs

|