|

Topping the Charts

In the last week of May 2005 something

happened in Britain that hadn't happened before. A new

number one single topped the charts the likes of which

may revolutionize the music industry. Another British

invasion, perhaps? Well, not exactly. The song itself is

17 years old, but a few months ago it was made into a

cell phone ringtone, and that is apparently what has

everybody so excited. Daniel Malmedahl's song "Crazy

Frog" which sampled some good-old-fashioned motorcycle

revving (which is always good when you can't think of an

idea) was reborn as "Crazy Frog Axel F" and was soon

making its omnipresence known throughout the world of

young people and their cell phones. Lest you think

society has gone completely mad, let me assure you that

there is no shortage of persons indignant that, as one

site puts it, the recent chart topper took its exulted

position ahead of, well, real songs, which is what the

pop charts traditionally consist of. The catchy ones and

the ones best publicized sell well, which makes them

chart toppers, and the rest get in there at number 182

or so. It isn't necessarily the quality of the music

that makes them sell--still, it can seem a bit

disorienting to think that it isn't even necessary to

throw a few words over a standard chord progression

anymore in order to capture top honors, sort of like a

hamster winning the Miss America pageant.

As I say, there are plenty of

people fired up about this, and some of the more

entertaining submissions can be read at a site called

engadget.com, under an article called "Crazy

frog ringtone tops British charts, beats out

actual music".

At least one person (namely reader

number 17) pointed out that it isn't the ringtone itself

that has topped the charts, but the song from which it

is derived. I imagine serious musicians everywhere are

heaving great sighs of relief. So is the music industry,

which sells the single for 3 pounds.

The band Coldplay, however, may be a

bit jealous, since it was their single "Speed of Sound"

that lost out to the cellphone ditty. I never really

considered Coldplay to be purveyors of great art.

One of the band's most popular songs, a great favorite

with some of my older piano students, has about as much

musical information in it as a phone number, and a whole

lot of repetition. But then, this is why it is popular

music. It is the kind of thing that gets in our heads

easily by being short, simple, and heard over and over

again. In that respect, it is not all that different

than what many of us hear on our cellphones, provided we

don't answer them for about three minutes.

I don't want to leave the

impression that there is anything glorious about

having a cellphone ditty outsell every other article

of musical noise in England, even if it is a bit fun

to see the music industry have to adapt its

monster-sized publicity machine to new uses, and read

scandalized citizen's reactions as they predictably

lament the end of civilization. Many of the above

site's readers said they would leave Britain, while

others called their countrymen imbeciles and many used

such colorful adjectives as I think I had better warn

those of you accustomed to the kind of gentility

regularly on display here frequently occur to those

who can't think of good literary

idea, either. Some of the most heated prophets of

societal entropy seem to have become so angry that

they have forgotten how to spell or use punctuation.

This is probably a result of a hidden message in the

ringtone that tells people to cave in to bad grammar.

But for those who are wondering if this

is indeed a new low in the history of British music, let

me assure you, it is not. Our one-time rulers have in

fact a long history of undeveloped taste in music. This

may in part stem from an abiding belief that music is

merely for recreation and entertainment; letters from

the leisure-class in 17th and 18th century England

routinely warn their progeny not too take too much of an

interest in such a low thing as music, manufacturing

being so much more respectable. Consequently, the

English manufactured some great pianos (Beethoven's

favorite, in fact, came from there) but no composers of

any real consequence for two centuries. But attitudes do

not always inflict themselves on a society from the top

down. Many increasingly prosperous middle class persons

wanted to show off their wealth and therefore status by

throwing their money at a frivolous thing like music,

and they required their young to learn to be fashionably

able at the piano as a consequence, thus instituting

another chapter in the long history of aping art mainly

in order to impress others.

This kind of art naturally requires

that it sound difficult without actually demanding too

much of the player and especially the listener. A few

days ago I was reminded of one such piece when I was

researching something else. It is from a genre known as

Battle Music, a kind of piece for solo piano, often to

be accompanied by noisy friends on percussion, or with

special pedals built into the piano for various effects.

The pieces, bereft of any real formal design, often

featuring a very shallow harmonic vocabulary or a

complete lack of genuinely arresting ideas, make up for

it in loud noises imitating cannon shots, bugle calls,

and other sounds of war, simple to imitate.

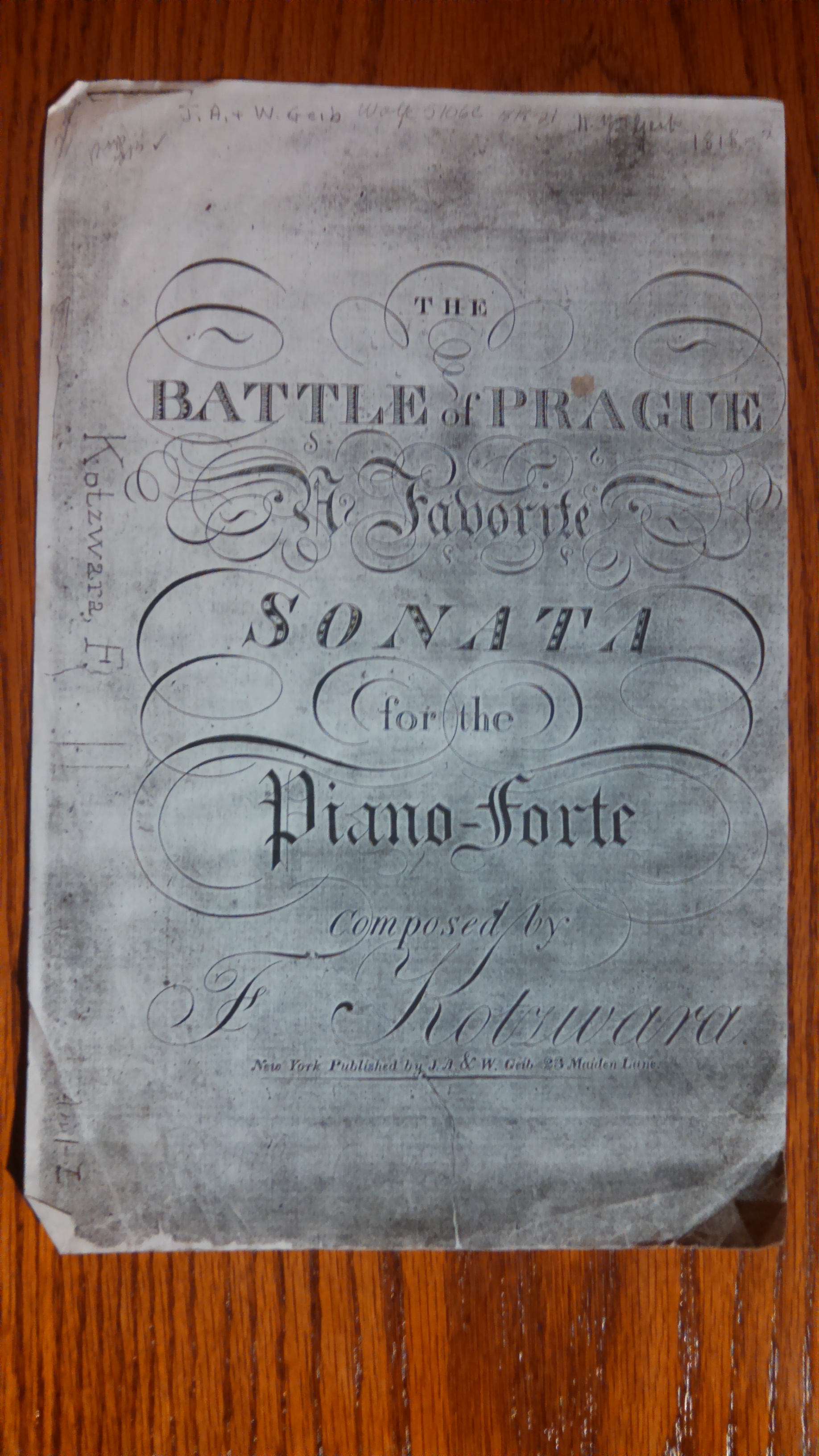

The piece I'm going to play for you is

called "The Battle of Prague" and it was the top

selling piece of British piano music for about half a

century (the first half of the 19th, to be

particular), which will probably make "Crazy Frog Axel

F" seem like a blip in the "going to hell in a hand

basket" category of musical outrages. Like its

brethren in the battle music class, it is accompanied

by an extensive narrative, which appears below.

I'm probably taking the piece quite a bit faster than

most amateurs did, which will make it sound more

substantial, if you aren't listening carefully. If you

are, you may notice that it is basically a lot of

typical formulas thrown around one after another

without actually going anywhere. The whole thing seems

rather well mannered, for a very bloody battle--the

real thing occurred between the Prussians and the

Austrians in 1757, which does not explain how the

Turkish music got in there.* Nor does it

explain the sudden appearance of God Save the King,

the very British national anthem (good of them to win

a battle in which they weren't actually involved),

unless we remember that all good Brits love their

country, and there is no good reason the Austrians

couldn't sacrifice a little historical accuracy for a

moment of patriotic chest-thumping on the part of the

people who bought the music.

|

The Battle of Prague: A

Favorite Sonata for Pianoforte by F.

Kotzwara

Slow March; Word of Command

(2:03);1st signal cannon (2:31); the bugle call

for the Cavalry (2:34); answer to the first

signal cannon (2:48); the trumpet call (2:50)

The Attack (3:07) [score is marked "Prussian

imperialists"] [low notes beginning at 3:21 are

marked "cannon"] ; flying bullets (3:44)

trumpets (4:28); Attack with swords (Right

hand)/horses galloping (left hand) (4:43);

Trumpet Light Dragoons Advancing (bass notes

marked "cannon") (5:00); heavy cannonade (5:09);

cannons and drums in general (5:27); running

fire (5:35); trumpet of recall (6:24) [those

last three flourishes in the bass are actually

marked "cannon"!];

Cries of the Wounded (6:48); The Trumpet

of Victory (8:05); God Save the King (8:29);

Turkish Music (9:42); Finale (10:10) ; Go to

Bed, Tom (10:55); Tempo Primo (11:02) [a return

to the original tempo of the finale]

|

Kind of makes war sound like a

lot of fun, doesn't it?

|