The Solace of Noble Minds

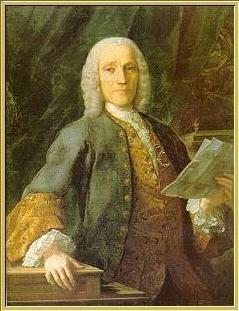

The Strange

Employment of Domenico Scarlatti

Naples in 1685 was a very loud place.

Thousands of inhabitants crammed into a tight

space, dwellings piled high atop each other,

narrow alleys filled with the cries of street

vendors, children, men rushing back and forth--a

cauldron of human activity. Into this noisy

environment was born one Domenico Scarlatti.

We know

very little about his life. He may have been

home schooled. His father, Alessandro, just

happened to be one of the most celebrated

opera composers in Italy, and he appears to

have taken more than a passing interest in his

son's development. One document that survives

records an attempt when Domenico was in his

thirties to achieve independence from his

father. In a place and time where no

coming-of-age was recognized, the elder

Scarlatti was able to make his children jump

when he wanted to. He once recalled another of

his sons from profitable employment in a

distant city to join him in Rome.

|

|

| If Scarlatti was not given

all his education at home, his schooling might

have been under the provenance of the

conservatory at Naples, a small building in

which one observer reported several

harpsichord players in one room practicing at

once, no two playing the same piece. The brass

players had to inhabit the stairwell, the

winds another room, the singers an upper

story--privacy was not a option. Scarlatti was

one of 10 children, and the first born into

the family after they moved to Naples.

Scarlatti himself relocated to Rome and to

Venice to seek employment. Possible trips to

Portugal and England have not been backed by

hard evidence. |

He spent most of his life in the

service of royalty. Being a musician--even a musical

genius--then as now did not mean an easy living. Two

of Scarlatti's great contemporaries illustrated

different solutions to the problem, and their

respective perils. George Frederic Handel, a German

in the service of the King of Hanover, left for

England to make his fortune in Italian opera. The

strategy worked until the public got tired of

Italian Opera. Handel then pinned his hopes on

Oratorio, but his financial status was frequently

precarious. Another German, Johann Sebastian Bach,

spent much of his life in service to the church. An

institution that was often slow to pay salaries and

that often paid them in foodstuffs, Bach was once

famously to complain that his pocketbook was getting

unfortunately small because few parishioners were

dying and he depended on the extra remuneration from

the funerals. Both men also spent some time in

the employ of persons of the nobility, whose

members' patronage was largely responsible for a

musician's livelihood in the days when public

concerts were a rare thing.

Scarlatti found an interesting

solution indeed. He had written operas, he had

written for the church, he was the typically Baroque

jack-of-all-trades. But he was to spend the rest of

his life immersed in the most neglected and least

profitable of musical enterprises at that time:

keyboard works. He became a music teacher with only

one pupil that we know of: the princess Maria

Barbara, soon to become the Queen of Spain.

What his duties at the court may

have included we don't know. Aside from contemporary

reports that he had a gambling problem, one

friendly letter and the dedicatory preface to the

single volume he published in life, we know nothing

of his personality, what he thought of his

situation, or what was expected of him. What we do

have are over 500 harpsichord sonatas of widely

varying character, unusual originality, impossible

technical demands, and thoroughly Spanish

flavor.

Scarlatti soon had to relocate

to Madrid, though the King and Queen spent only a

scant portion of the year there as they traveled to

other palaces with clocklike regularity. His

activity may have been largely restricted to the

palace; in any case, scholars have to confront the

problem of a complete absence of manuscripts in the

composer's own hand, as well as an astonishing lack

of contemporary copies of the sonatas in Spain or of

any references among musicians of the day, and are

left to conclude that the Queen may have required a

monopoly on his talents.

We know more about one of

Scarlatti's colleagues at the Spanish court. This

was a castrati singer named Farinelli. Reputed to be

the greatest singer of his time, the man was engaged

to sing the same four pieces nightly to help the

king's depression. Scarlatti may have accompanied

him at the harpsichord on such occasions. As a

condition of his employment, Farinelli was not

allowed to offer his services outside of the palace.

It is odd that this restrictive gig did not bother

the genial singer, but his services to Scarlatti's

legacy are massive: on the death of the king, his

heir terminated Farinelli's employment, and

Farinelli took with him the only two copies in

existence of the (perhaps) complete sonatas of

Scarlatti, which have since come to light in two

cities in Italy. Until the later 20th century,

these were our only authentic sources for

Scarlatti's pieces.

| Scarlatti's

works are in some respects almost a diary:

courtly pomp figures in, as do dances of all

kinds, noble and popular. Cries of street

vendors and children's games are represented.

None of this is part of any kind of overt

storyline. Instead, Scarlatti made the

single-movement Sonata in two-part form the

vehicle for his thoughts and moods. It was a

scheme he was to employ without variation some

555 times. But within that broadly conceived

form are hundreds of very different sonatas.

Scarlatti modulates into the same keys over and

over and over again. How he gets there

is another matter.

Biographers have

speculated that Scarlatti was a fiery

personality, perhaps even manic. He may have

written his pieces under a sudden burst of

inspiration and then abandoned the

harpsichord for days. We cannot be sure. His

works are full of the noise and activity he

must have known from his Venetian youth but

thoroughly transplanted to Spain. It is the

strange fate of Spain that much of its most

characteristic music was written by

foreigners!

|

The Queen was apparently

impressed with her music teacher. Before becoming

Queen she actually hired him on two separate

occasions. And Scarlatti served at the Spanish court

for over twenty years, until his death in 1757. His

Sonatas must have given her quite a challenge if she

played them. His notorious hand-crossings and

reckless leaps make for a real technical challenge

even in our own day. This is music of a virtuoso

risk-taker. But his Sonatas also explore all manner

of strange harmonic possibilities with sudden

dissonance and unpredictable changes of texture. It

was probably for this reason that an observer

referred to his pieces as "happy freaks" and their

strange modernisms may be what has kept them tucked

away in a neglected corner of the repertory for so

long.

Scarlatti himself could

certainly play them. One witness told how when

Scarlatti began to play it sounded "as if ten

thousand devils" were animating the

instrument. At Scarlatti's disposal in the

palace were several instruments, some of which had

ranges wider than that of Mozart's and Beethoven's

pianos. There was an early piano there as well;

evidently Scarlatti was so impressed with it he had

it converted to a harpsichord!

He must have had a limited

audience. The queen may have had a musical ear, but

the king did not care for music, at least until

Farinelli arrived to awaken him, as the story goes,

from one of his frequent bouts of melancholy. The

king represented the second generation of not very

mentally stable kings in Spain; both of their queens

really ruled the realm. How intrigued he might have

been by Scarlatti's "happy freaks" and strange

inventions we'll never know, but, given his

predilection for listening to the same four arias

night after night, it is more than likely that

Scarlatti's greatest inventions were only

appreciated by half his potential audience.

Scarlatti was genial when it

mattered: knowing the difficulties of a musician's

life and the plumb arrangement he had with his royal

patron, who allowed him time and circumstance to

develop his flights of genius, he took the occasion

on publishing some of his sonatas (here called

"exercises") to flatter the king in the manner of

the times. Some of it must have been genuine:

| To the

Sacred Royal Majesty of John V.... The

magnanimity of Your Majesty in works of

virtue, your generosity in others, your

knowledge of the sciences and the arts and

your munificence in rewarding them are

well-known attributes of your great

nature.... By universal acclamation you are

known as the Just: a title which embraces

all other glorious ones, since good works

serve no useful purpose unless they are acts

of justice to oneself and others....Music,

the solace of noble minds, granted me this

enviable good fortune, and made me happy in

pleasing with it the most refined taste of

Your Majesty.... |

For whatever reasons no further

publications were forthcoming despite Scarlatti's

introductory promise to make the contents of the

next volume simpler for the amateur. With

typically Baroque false modesty the composer claimed

to explore no profound depths in these pieces, only

an "ingenious jesting with art." For the rest of his

life he would follow the royal procession in its

rounds, making the palace walls ring with the sound

of his harpsichord. Oh to be a fly on the wall!

|